In terms of migratory drama, monarchs are the diminutive wildebeests of the sky. They are the only butterflies that make a two-way migration like birds. But no single butterfly makes the entire journey. Instead it is like a relay race, with four generations passing the butterfly baton in order to fly to their northern summer homes and back to Mexico for winter.

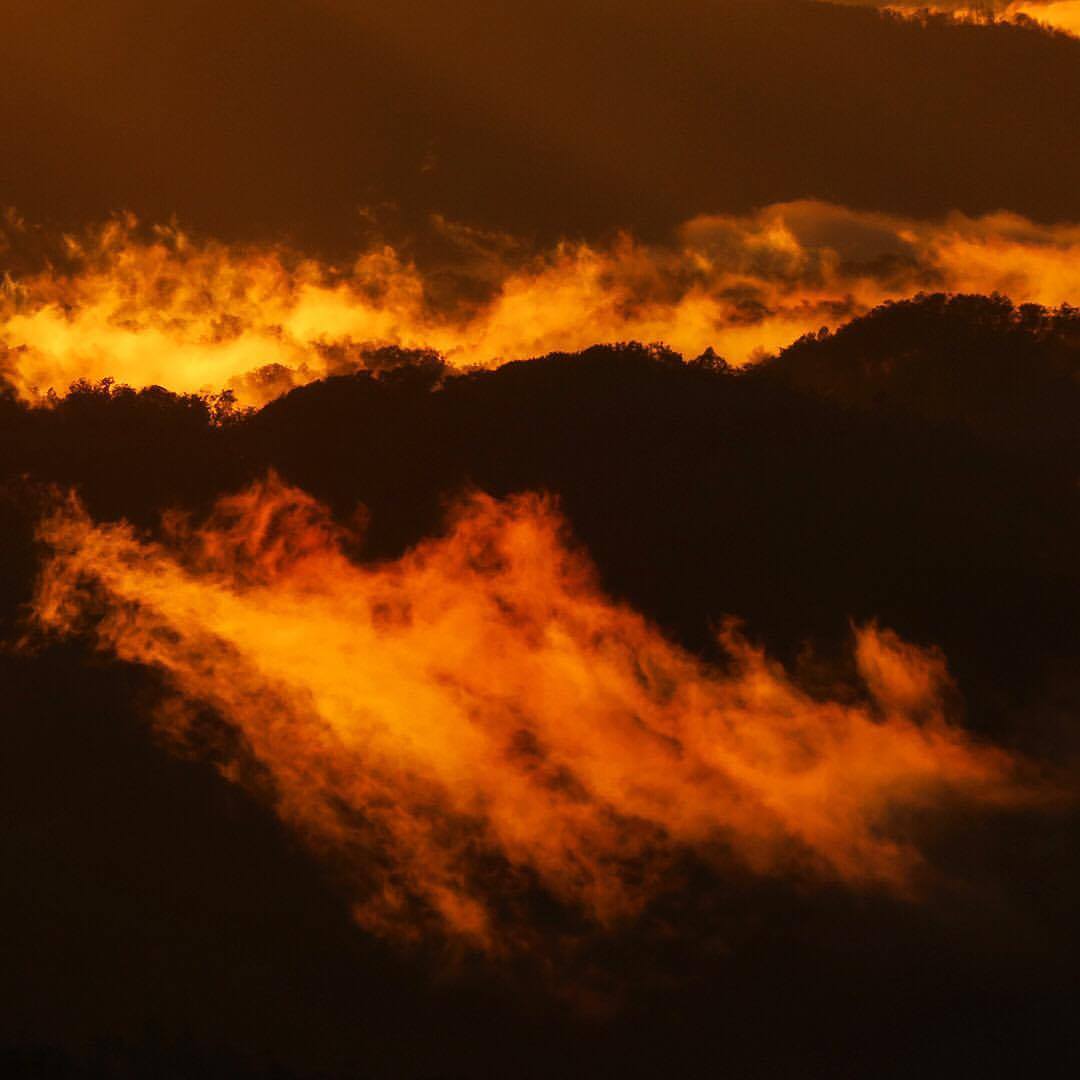

At this time of year in the southern Appalachians, monarch butterflies reach their peak of southern migration through mountain passes en route to their winter home. Some have already traveled thousands of miles, and their journey is far from over.

They fly south about 50 miles a day, using air currents and thermals to extend their flight. They take advantage of northern winds to go further, and rest on days with strong southern winds. Depending on their start point, this trip can take a couple months.

The butterflies now are the fourth and final generation of the relay team. They are larger than the northward traveling generations, since they will live long and fly far. They come now to gardens, fueling up on nectar from plants like these aster flowers that not only will sustain their voyage, but also keep them alive through winter.

These butterflies will hibernate in groves of forests in the highlands of southern Mexico, huddled together for warmth. They will become active in February and March and head north on tattered wings to lay eggs in the southern U.S. before dying. This is the start of a new generation, the ones that will continue the journey north, with spring.

Each butterfly goes through a further personal relay of four stages, from egg to caterpillar, chrysalis and adult. These summer butterflies only live around 6 weeks, just long enough to create a new generation. They lay their eggs on milkweed, the primary food source for their caterpillars, which can consume an entire leaf in only five minutes. They feed voraciously and grow quickly, racing time and creating two more generations for the butterflies to reach the far north, their summer breeding grounds in the northern U.S. and Canada.

Earlier this year the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service released findings showing that almost a billion monarchs have disappeared in the past 25 years. One of the main causes is the use of weed killers, of special concern in the Midwest where genetically modified seeds create crops that resist herbicides that are then used to kill nearby plants, including the plant that for monarchs is more milk than weed. It is believed that the milkweed habitat there is almost gone, with nearly 150 million acres lost.

Just yesterday the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, established to support the mission of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, announced grants of $3.3 million for the newly created Monarch Butterfly Conservation Fund. This will be matched by more than $6.7 million in additional contributions. The money will be used primarily to restore native milkweed populations. In a hopeful sign, Monsanto has provided a considerable amount of funding, perhaps in recognition that their herbicide Roundup Ready has had a major negative impact in destroying milkweed.

It is hoped that efforts to conserve their winter homes in Mexico, along with this new funding to help preserve their migratory pathways and northern homes here in the U.S., will help these important pollinators rebound. If not, maybe their trip on the International Space Station in 2009 is just the trial run for their ultimate migratory destination, the colonization of space!